The first photo Janet took of me was at an exhibition opening. We were at Auckland Art Gallery for the mega-affair that was the 5th Auckland Triennial: If you were to live here . . . As we left the gallery, a group of us attempted to sober our sloppy smiles and pose for the camera at a friend’s request. Later that night on Facebook, I found Janet had taken a photo of the photo being taken. Her version, however, featured a characteristic J. Lilo twist: Photoshopped in front of the foyer’s revolving doors was a crocodile, nonchalantly photobombing our careful poses. Janet created something similar from the next opening we were at together, this time replacing one face in that obligatory group photo with a chicken mask and another with the ‘Ghostface’ mask made famous through the Scream horror film franchise and subsequent Scary Movie parodies. In fact, many social events that Janet has attended have been followed with a photo that she has humorously improved. One of my favourites comes from a colleague’s leaving drinks, where all the cans of beer have been replaced with cans of Wattie’s baked beans.

These Facebook images are just a small example of Janet’s obsession with all things image-related. Part of what makes Janet’s documentation practice so distinctive is that she truly thinks of it as practice: she’s rarely seen without her camera and is constantly editing, which makes her highly adept with the different ways an image can be manipulated. Cropping, inserting, utilising colour saturation, applying filters, lassoing, cloning and layering are just a few of the techniques she regularly uses. The resulting images exist in both private and professional spaces. When she was still active on social media, many of these digitally collaged works were uploaded on Facebook – Janet now often attaches them to personal emails. Other images are presented more formally as artworks, though still in sites as diverse as YouTube, outdoor venues and gallery spaces. Image manipulation is such an integral part of Janet’s modus operandi that we were originally going to call her survey exhibition ‘Cut and Paste’, until we learned that title was already taken by an upcoming exhibition at The Dowse.

Janet’s editing fixation stems, in part, from the desire to master the possibilities and understand the implications of making images in a digital age. Because a digital image is essentially a data file, comprised of bits of information, rather than imprinted on film, it can be edited with relative ease and speed using software, radicalising how we construct images. Though this media revolution is fairly recent, its uptake has been both rapid and universal. Retouched photos and CGI are normalised influences in the media we consume. More significantly, editing functions have quickly become embedded in even the most basic devices – no longer do you need to be a Photoshop pro to make use of image manipulation tools. With cameras now standard on nearly every digital device, easy-to-use, in-built editing functions can be found on most phones and computers. There is a multitude of websites that allow you to edit photos online: you can create virtual makeovers, animated gifs, dubbed videos and more. Janet’s current practice exists within an image culture in which a Keanu Reeves photo can spawn an infinite number of memes in just hours, and knowing how to turn out a flattering selfie is pretty much a given.

With constant upgrades to digital devices and software, it seems that many of us are occupied less with understanding the capacities of each new tool and more with simply trying to keep up and avoid our own obsolescence. The result, media theorist Douglas Ruskoff argues, is that ‘we have embraced the new technologies and literacies of our age without actually learning how they work and work on us’.[i] He continues: ‘only an elite – sometimes a new elite, but an elite nonetheless – gains the ability to fully exploit the new medium on offer. The rest learn to be satisfied with gaining the ability offered by the last new medium . . . As a result, most of society remains one full dimensional leap of awareness and capability behind the few who manage to monopolize access to the real power of any media age’.[ii]

Rushkoff points his readers towards a certain power imbalance embedded within digital technology, the effect being that we, as users, are unwittingly complicit with the biases entrenched in various software and devices; tools that very few of us understand from a programming perspective. Indeed, there’s an unacknowledged tension that comes with digital imaging: it has ushered in a new way of making images that is both incredibly accessible yet almost entirely pre-determined. There are certain editing functions – such as drawing or writing text on top of an image in Snapchat or changing the colouration of an image using a filter in Instagram – that have become popular precisely because they are pre-provided options. As Janet notes: ‘we use these options because they seemingly improve the image through a digital process, but ultimately you do it because you are given the license.’[iii]

Janet adamantly resists being programmed. Apparent across much of her practice is a desire to be an alert user of all things digital. Many of her works are underpinned by an investigation into how newly introduced technologies work and work on us: how do they impact our aesthetic impulses and in what ways do they shape the type of images we make and the way in which we make them? These questions often necessitate working in an experimental manner, a characteristic that defines Janet’s practice. Cry Me A River (2004), for example, is an early work that employed the then newly introduced digital camcorder. Though it seems a given now, camcorders introduced a viewing screen, or viewfinder, to the video camera, so that the documenter was no longer limited to just looking through the lens. More significantly, the viewfinder could be flipped 180 degrees, allowing the person being documented to see him- or herself in the frame as he or she was being recorded.

Cry Me a River (a split screen video of one woman singing and another lip-syncing to Justin Timberlake’s track of that name) experimented with the new self-awareness a viewfinder offered subjects. Both performers ham it up for the camera as they simultaneously view the self-image they project to the unknown viewer. The work could even be considered a moving-image selfie: a precursor to the fascination with capturing our own image that would explode with the introduction of the front-facing camera.

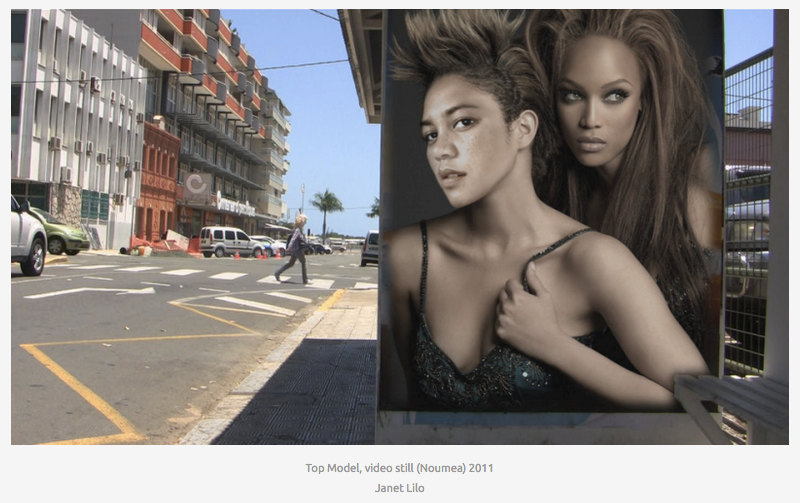

The digital technology that Janet utilises and investigates most often, however, is Photoshop. Top Model (2011) is a series of 16 images made during a three-week residency in Noumea. The works were made by taking selfies using Photo Booth software and a webcam on a Mac laptop, then superimposing these captured poses over the faces of every Top Model winner across 16 seasons (or ‘cycles’, as host Tyra calls them). These collages were then (again) superimposed onto billboards Janet had photographed in situ in Noumea. The series in part functions as play: a test of how successfully Janet can pull off the trompe l’œil effect of turning herself into a top model. It also serves as practice: on her website, Janet notes that she was still becoming accustomed to using Photoshop software, so the images provided an opportunity to try ‘to get it right’.[iv]

Top Model also, perhaps unintentionally, highlights the role of Photoshop in changing the status of existing images. With the increased editing capacity that software introduces, any and all existing images become potential raw material for new creations. Limor Shifman, a communications lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, calls images made by reworking an existing one ‘Reaction Photoshops.’[v] She argues that people are particularly likely to rework existing images if the originals seem overly contrived, using humorous amendments to foreground the constructed or staged nature of the original image.[vi] Janet’s Top Model could be seen to fit within this framework: using Photoshop to destabilise the certainty (and sanctity) of popular images, specifically in Top Model as they relate to normalised beauty aspirations and ideals.[vii] Notably, Janet’s aesthetics often foreground the constructed nature of her digital manipulations. Mirroring, colour saturation, silhouetting and cropping are all unabashed evidence of editing that even the most stubborn Luddite can recognise from widely used programmes such as Photo Booth. Though a greater accessibility to the means to digitally amend images carries the potential to better recognise local realities (Janet’s version of Top Model inserts a brown face into fictional billboards located in a Pacific nation where most billboards feature white models), a conscious and visible recognition of the role of digital editing drives both the intent and the aesthetic of Janet’s works.

Despite, or perhaps rather because of its far-reaching influences, Janet has recently shied away from digital software and returned to using analogue processes. In 2014, she walked the entire 80-kilometre distance between the French cities of Le Havre and Rouen as research for the group exhibition, Pacifique(s) contemporain (2015). Along the way, Janet selected two objects as points of departure for a new body of work: a high-vis fluoro vest and a mesh cylinder used to surround newly planted trees. These two items of protection were the starting points for an elaborate drawing series undertaken back home in Avondale, Auckland. During a recent studio visit, Janet pulled out page after page of drawings at A5, A4 and A3 sizes that teased out different ways that these two objects could be drawn. The drawings differ by small permutations. One image uses duct tape, the next uses duct tape with one strip placed at a slightly different angle. Two other images are distinguishable only by the different density of the cross-hatching. The effect acknowledges, mirrors and dissects the speed and ease with which we create different versions of an image on our screens, all with the speed of a mouse click. As Janet explained, ‘If I could make the digital quickly, it’s relevant to challenge myself to do that in analogue too.’[viii]

Though critical of digital imaging’s largely unquestioned impact, Janet’s approach isn’t to vilify. In a time when almost everyone has the power to capture, distort and distribute images, Janet has pressed pause. Like her interview works in which her voice can be heard questioning the people we see on screen, her images deliberately evidence the digital hand of Janet as editor, gleefully refusing any naturalisation of digital influences. To return to Koskoff: ‘[w]hat is called for now is a human response to the evolution of these technologies all around us.’[ix] In Janet’s hands, the digital is re-humanised: it is programmed technology used by a conscious mind. Her practice teases out and exploits the possibilities of an all-encompassing technological revolution, while warning of the danger of not being exploited in return.

[i] Douglas Rushkoff, Program or be Programmed: Ten Commands for a Digital Age, New York: OR Books, 2010, p. 13.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Janet Lilo, interview with the artist, Avondale, Auckland, 23 February 2016.

[iv] Janet Lilo, http://janetliloart.com/2012/10/05/brothers/, accessed on 2 March 2016.

[v] Limor Shifman, ‘The Cultural Logic of Photo-Based Meme Genres’, Journal of Visual Culture, 13(3), 2014, pp. 340–58.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] In an episode of Fresh (accessible on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4FbucU6gxI), Janet notes that Top Model was in part influenced by becoming a first-time mother who was coming to terms with her new body, mind and lifestyle, and who found humour in the idea that any body could be a ‘Top Model’.

[viii] Janet Lilo, interview with the artist, Avondale, Auckland, 23 February 2016.

[ix] Rushkoff, p. 13.